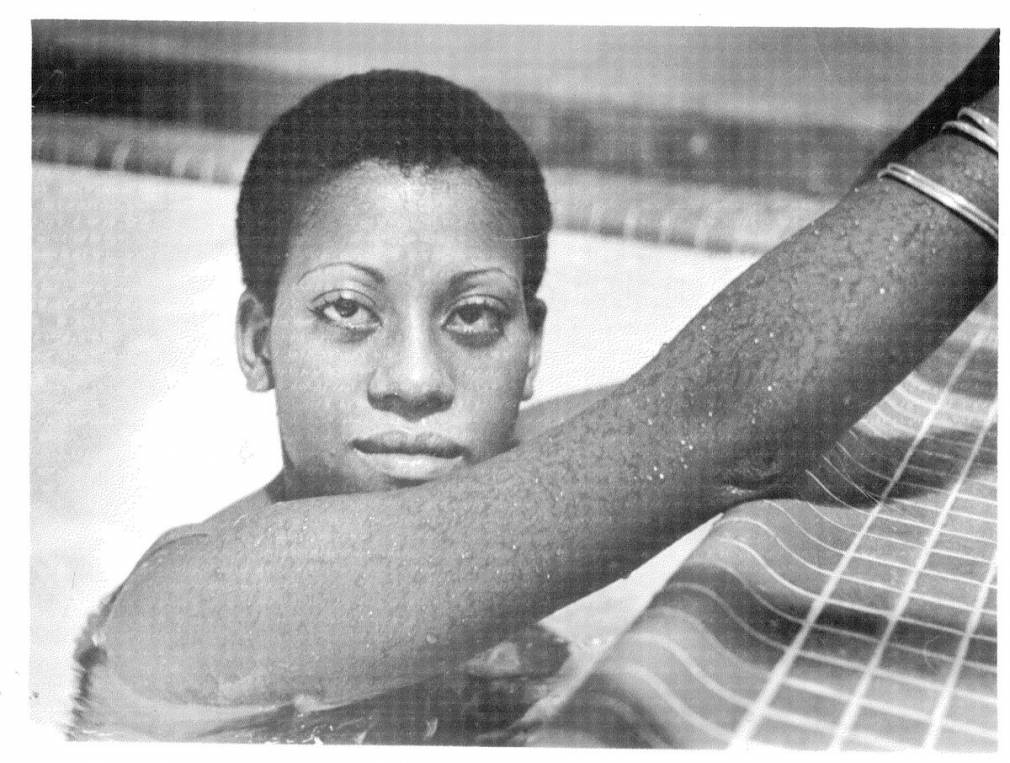

Without Mariette Auvray’s The Keeper, soon to be released on PAM’s YouTube channel, you – like me – might never have gotten to know Cheryl Ann Bolden. What a shame that would have been! This mature, thoughtful, chatty, sensitive and funny woman has a pretty atypical background. First and foremost she has developed a relationship with history through objects, and the intimate relationships we all have with them. Cheryl recounts history – both her personal story and the histories of Black people – by letting you touch personal objects and documents that she has been given or that she has found. Getting close to these relics of the past is a way of bringing back to life the great many forgotten ones of ‘official history,’ that which is told by the victors. Born in New Jersey, daughter of one of the city’s first black firemen, this insatiable researcher travelled around the world – with stopovers in several African countries – before settling in Paris a little over twenty years ago. She has set up her workshop-museum called Precious Cargo in Aubervilliers near Paris, and doesn’t hesitate to take it into schools in order to question stereotypes and encourage discussion with younger generations.

Before discovering her work on May 7th via Auvray’s documentary, The Keeper, let PAM introduce you. The conversation is enriching…and funky.

Cheryl, you’re a sixth generation African-American, have you been searching for your family genealogy in the US?

A little bit. We know that in Georgia there was a British man who had slaves. I haven’t done real indepth research but I can trace it back to my grandmother, my great grandmother, and great-great grandmother. But I don’t know exactly where I am from in Africa, which is not a problem for me, it’s ok, actually it’s better in a way that I can be from all of Africa. But for me this idea of being American and African, it’s very important. First of all, since the times of slavery we were considered Africans. It’s not a new thing. We didn’t come from China, or Russia, we came from Africa. And then, of course, we were called colored (like in South Africa), Negro and of course Nigger – which is a negative word, but African-American was an affirmation of pride in your heritage. The affirmation of being African gives you a sense of pride. If all your pride has been taken away from you, the idea – and it’s revolutionary- is to assume Africa. The old way to think was: “Africa is bad, everybody is poor…” (we have problems for lots of reasons, but that’s another discussion), but to assume Africa as your land. Also, in the Sixties, there’s this idea of self esteem : wearing your hair in a natural way for example, thanks to new concepts of beauty. What is beauty? Who decides what beauty is? So, I started dreading when I was a teenager, and of course I was in Catholic school so it didn’t go well, and my grandmother was shocked. But for me, as I had very thick hair, dreadlocks were the most natural thing to do. And I discovered that hanging out in New York in the Village or in Harlem, and meeting African-American people who had dreadlocks back in the seventies. So I was kind of balanced in being a hippie, but also being proactive in terms of my africanism and pan-africanism. But also just understanding that I am a true American woman. This idea of the “Yes we can” kind of attitude isn’t just reserved for white folks. That, as a woman of color, I have rights just like any other American, and at an early age I had to fight for that. I didn’t really understand it, but it has been a continuous thing in my life : dealing with race.

How did this passion of collecting things and keeping their memory come to you?

I like to say I’m a “clochard”. After studying acupuncture, I wanted to study in China and wanted to be a barefoot doctor where you go into the villages and take care of people. So I decided to try studying in China but at that time the country was closed. So I got a job teaching swimming in Alaska, and through the University of Alaska, I got a possibility to study in Beijing (I used independent study and part of this study was about medical anthropology, alternative medical techniques that were unprofitable – that was important for me). I was never a communist or whatever but I wanted to see what else was going on in the world. So for me China was interesting. However, after being there, it was really depressing. I was supposed to stay for 5 years, but I definitely couldn’t have done that. So I moved to Australia.

But each place I went… in Alaska for example, the Native people wanted me to speak about African-American history and culture, so I was put into this diplomacy kind of position to speak about my culture. Then in China at the University they asked me to speak about the Black experience. After I went to Australia, and again I spoke about Black History. I didn’t understand the importance of African American history and culture outside of the US. You are kind of put into it when people begin to ask you. And I started to think about my ancestors not as victims : as being enslaved – and we use the word “enslaved” as opposed to being “a slave”. So I began to see my ancestors as being enslaved, they were humans and they were more than just victims.

In Australia, I had met Aborigenal people. The Natives had the same problems as we African-Americans had. People whose land had been taken away from them. If you take the land away from people who are living on it, they lose their culture and they drink and they kill each other and they die. So I began to see this connection again with the Maoris in New Zealand, and even in China with the darker Chinese or the Ouigour…

So finally after Australia I returned to the US in the early 80’s with the idea that I wanted to do more research about American history and culture from a different perspective. I took a job at James Monroe’s house, Ash Lawn, near Monticello (Thomas Jefferson’s house) and at that time the historical societies were not open to talking about enslaved people (we knew about Frederick Douglas and so many other people), but the history was still kind of undercover. It wasn’t mixed in with American culture. You are American but then you have that separated culture, the so called “enslaved” cultures, who are human beings, and essentially built the United States… for free. So I took a job as a guide at this house, and I remember talking about the paintings and the furniture, and then you had the enslaved people’s cabins, but we were never really instructed to talk about those people. It was sort of a taboo to talk about slavery… but wait a minute, the people like Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, so many other slave owners, if it wasn’t for those enslaved people, they wouldn’t have been able to do what they did. That’s the reality. So when people say “oh it happened so long ago”, the fact is that some of the laws that were made back then are still being used today to keep people of color down. That’s the consciousness of understanding African Americans as true Americans, and that we contributed to the growth of the country. Oh.. and then I got fired!

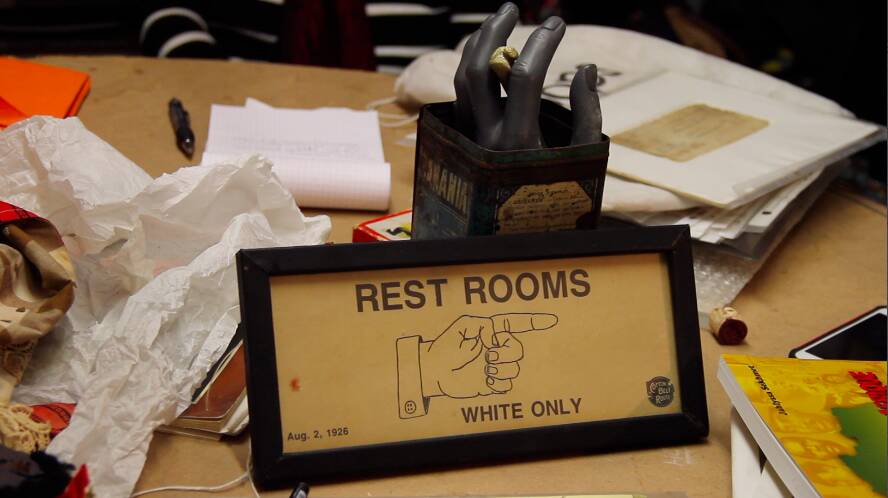

So I opened up a gallery : Bolden Gallery and museum Precious Cargo. Some of the people in the community began to give me documents related to Slaves that their families might have had. I have some documents related to taxes because if you had a slave, he was considered your property, and you would pay personal property tax, so it was listed “Two Negroes, etc…”. People saw that I was collecting and they started giving to me. I didn’t understand how important that was at that time (it was maybe in 85-86). Then I realized it was a sign. Looking at it visually it’s a beautiful piece of art, but it also says a lot when you have “two Negroes “ and “5 horses” on the same line. It shows the value of a human next to an animal. So that for me was such an important aspect of starting a collection. Then I started collecting things from the family, and we had antique shops where I would buy anything that I saw that had anything related to Black people on it. That’s how Museum Precious Cargo started.

When was your first trip to Africa? I guess that for you, as for many African-Americans, it was something important…

Actually, in Newark, we had African people. And Harlem was like Africa. When I was living in China I met the Ambassador from Senegal so when I went to Senegal for the first time, in 1985, I had some places to go. Of course it was like, “Oh my Goodness, it’s beautiful!” It was a great experience to go to Gorée island where the slaves left to go to the US. I mean that was sad, and I felt the energy of the enslaved people in these places… you know it was great to see all these beautiful people running this country. And I saw that it was French, you could see the colonial aspect of it too, which was quite interesting. And pretty much I would just go buying (my gallery was basically an African Art gallery) and travelled around by bus, or train or car, and I traveled the coast : Togo, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria I stayed in Lagos, Kenya, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe…. I remember, I went to the South African border, it was before apartheid was, as they say, “eliminated”, and I remember on the border thinking, “I’m not sure if I want to go to South Africa at this point, maybe it’s not a good idea with dreads to go to South Africa.” So I didn’t go. Yes, I was very affected by Africa.

Making a bold shortcut into your history, in the early 90’s you settled in Portugal, then Germany, UK, Mexico… What brought you to France?

My daughter was born when I was in London. I went to Mexico to live near the beach with her, and then I met a German man who was a Sorbonne doctor. When my baby was two years old, we got installed in the 5ème arrondissement in Paris. So that’s why I am here. And I stayed. I was in love. I had a child. We were supposed to get married, but we didn’t, so that put me in a very bad position here, not being legal. So I understand this idea of not having papers, particularly being black. But I was lucky enough to meet nice people in the public social services who helped me to get my “carte de séjour”. Then I got support from the American Embassy to go with my museum Precious Cargo in the schools, and that’s how this idea of a “musée itinerant” started; going into the schools and bringing the original documents and art to speak about history from the perspective of an artist.

What do you mean by “speaking about history from the perspective of an artist”?

Because I have been blessed to have a very decent life, I integrate my personal narrative. So when you look at a document, you can reinterpret it to make it more real for the person you are speaking to, as opposed to having something behind a glass case. For example, I have slave chains that you can pick up and touch. I think as an artist, you can open up the conversation about what something could mean, and again my own personal experience to humanize it because sometimes history, particularly on an academic level. Even if it’s really good and precise, for the most part, one must ask, “How does that relate to your life? How does it affect what happened to somebody in your community?” for example. I’m not a historian and I’m not an activist, but as an artist I can put my own spin on things. The personal narrative aspect helps people to open their mind a little bit more, and to do their research. People need to research. There is so much information around us now. There is no excuse not to know about certain things.

You were talking about mixing personal narratives (yours and the narrative of the people who gave you these objects), but there is also this dimension that we see in the documentary, when you allow people to touch the objects. Why is it important ?

Well, it’s called “Museum Precious Cargo” for a reason. I believe museums are wonderful for the educational and artistic dimension, but normally in the museums you can’t touch things. So the idea of visual culture is that you can learn how to touch things and to experience their value. The value of keeping things that your grandmother might have thrown away, like letters or photographs. And to see how important those documents are for preservation. And also, for example, the chains of enslaved people, when you pick them up, they are kind of heavy – so this idea of what it felt like if you wore chains around your ankles. When I do things in the schools, some people are freaked out, and others want to put it on and play, and they literally play with it… which is great, they transformed it. It’s not so much, “oh my god it’s so heavy”. It is very heavy duty, but on the other hand, playing with it, I think, opens up the spirit, it gets out the energy. It comes full circle when you play with it, but you respect it. You get the energy from it, open it up, feel the texture… Also this idea of museums and academia that tends to put people on a pedestal, it creates distance. Getting young people to understand that you don’t have to have a PHD to know about history: if you want to do that, I encourage you to do so, but you don’t have to have a PHD to do it. You can open up your own museum, you can do these kinds of things without having all the paperwork! I think this is very important, this idea of transcending the way we see education, particularly now. Who is going to the big schools? Who has the right to transmit information? Who is interpreting this information? I think that is something important.

From 7 May, PAM’s YouTube channel will feature Cheryl Ann Bolden in The Keeper, a portrait of her by director Mariette Auvray. Don’t forget to click on the bell on the YouTube Premiere.